- Home

- Lilas Taha

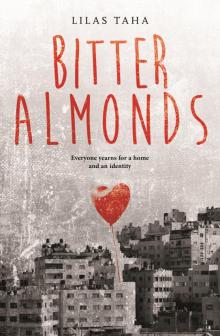

Bitter Almonds

Bitter Almonds Read online

Also by Lilas Taha:

Shadows of Damascus

LILAS TAHA

To the loving memory of my father

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Acknowledgments

1

Jerusalem

1948

They told five-year-old Fatimah not to turn around, but no one told her to close her eyes. No one told her not to listen. She pressed her face against the window, a rag doll forgotten in her lap. Quiet rain speckled the cold glass, and a flickering street lamp cast broken yellow beams on the desolate street. Fatimah sat mute, comforted by the soft drizzle, and watched the scene behind her unfold on the reflective pane. If she sat very still, they might forget she was there.

Her mother pushed aside the midwife’s fussy hands and scooted her huge body to the edge of the bed. Grunting, Mama got to her feet. She yanked at the collar of her cotton gown, ripping the front buttons and exposing her sweat-drenched chest. She spread her legs wide apart. Fluids trickled down and dampened the hem of her gown and the faded rug.

‘Get back on the bed,’ the midwife instructed in a raspy smoker’s voice.

‘I can do this,’ Mama panted. ‘Baby is coming. I can feel it.’

‘Do as I say.’ The midwife brought her wrinkled face close to Mama’s. ‘Your baby needs help. You will not be able to push it out by yourself. You’ve been trying all day, and the night—’

The door flew open. The next-door neighbor, Subhia, walked in. She closed the door and rolled up her sleeves. ‘How can I help?’

The midwife slid her hands under Mama’s arms and attempted to get her back on the bed. ‘Come. Help me before it’s too late. Lift her legs.’

‘We should’ve taken her to the clinic.’ Subhia bent to hold Mama’s feet. ‘Now it’s too late. Everyone in the village has left.’

‘She’s stubborn. If she had done what I said, this baby would be out by now.’

Quick knocks shook the wooden door. The women froze.

‘We have to go.’ Subhia’s husband urged from behind the closed door.

‘I can’t leave her now, Mustafa!’ Subhia shouted over her shoulder.

‘The gangs are bound to head this way. I’m not waiting any longer. The children are in the truck. I’ll make room for the women. Hurry!’

Subhia gripped the midwife’s arm. ‘What do you think?’

‘We can’t even get her back on the bed.’ The midwife shook her head. ‘And I’m not leaving her. Go with your husband.’

With a loud cry, Mama squatted, bringing down the two women beside her. She gripped the edge of the bed and held her breath. Her face turned crimson and her eyes welded tight.

‘Stupid woman, stop pushing. It’s not time!’ the midwife yelled. ‘You’ll hurt yourself.’

‘I don’t care. The baby is here!’ Mama screamed the words. She then screamed for her own mother. Screamed for her dead husband. Screamed for God to help her, to protect her baby, to end her misery. Screamed until her voice failed her.

For a brief moment, a suspended instant in time, all the noises of the world disappeared. No raindrops tapped the window in front of Fatimah’s face. No women frantically bellowed instructions to her mother. No panicked neighbor banged on the door. Only one sound could be heard.

A gasp.

A cry.

Fatimah ran to Mama’s side, forgetting to remain invisible. ‘A boy?’

The women ignored her.

‘Oh, Mama, look at his hair,’ Fatimah whispered, surprised by the wispy red fuzz.

The midwife wrapped the baby with a towel. She placed her lips over his nose and mouth and sucked hard, her cheeks sinking deeper in her bony face. She pulled back, spat on the soiled rug and repeated the process several times. She thrust the baby into Mama’s trembling hands.

Another knock shook the door. ‘Subhia, please. We have to leave now.’

Mama touched her lips to the baby’s forehead. The simple movement drained whatever energy she had left. Her head dropped back on the bed’s edge, eyes closed. ‘Take him,’ she mouthed.

Fatimah smoothed back hair off Mama’s damp forehead. ‘I will help you take care of him, Mama.’

Subhia cradled the boy, her eyes searching the midwife’s face, grim and ominous.

‘I’m coming in!’ Mustafa shouted from outside.

The midwife snatched a blanket off the bed and covered most of Mama’s body.

Mustafa stormed in, took his wife by the shoulders and pulled her to her feet. ‘Get in the truck.’ He knelt on the floor. ‘Grab whatever you need. I’m taking you out of here.’

‘Go. Take Fatimah too. I’ll stay with her.’ The midwife swatted away his hands. ‘Take your family.’

‘I’m not leaving you two behind. There’s no one left. You’ll tend to her on the road until we get to the next town. If it’s safe, I’ll find a doctor.’

‘She will bleed to death if you move her.’

‘And you will both die if you stay. You heard what Stern and Irgun gangs did in Deir Yassin. They butchered people, women and children. They will do the same once they get here. Now stop talking and get moving, old woman.’

Subhia settled on a pile of blankets in the truck bed. She had the baby in her arms. Her three-month-old son, Shareef, slept in the arms of his eight-year-old sister, Huda. The plastic tarp shielding them from rain sagged in the middle and rested on Subhia’s head.

Fatimah squeezed her little body next to Huda’s and placed Mama’s head in her lap.

The midwife climbed in. She worked on getting Mama into a comfortable position.

‘Did you remember to lock the door?’ Subhia asked.

‘I did.’ The midwife patted her chest. ‘I have the house key here.’

‘We’ll be back in a couple of weeks.’ Mustafa slammed the truck tailgate. ‘Once this is over.’

2

Damascus

Ten years later, 1958

Fatimah balanced a laundry basket on her head, gathered the hem of her long dress with one hand and climbed the stairs to the roof. She pushed open the metal door and walked out to a bright day. Sagging ropes crisscrossed the wide open area. She used every inch of the clothesline to hang her wet load, working as fast as she could, humming all the while. She had other chores to take care of, but doing laundry for the big family was a full-day chore. This was her sixth and final load. She had started at dawn and now the midday sun would finish the job. She flipped the empty basket to drain the water and stretched her back.

A boy shouted a series of profanities from the street. Fatimah knew that voice, but she ran to the railing to check anyw

ay. Her brother stood in the middle of a ring of boys, all older and bigger than him.

‘Omar!’ she yelled. ‘Meet me at the bottom of the stairs!’

Omar looked up and scowled at his sister for interrupting the scuffle. He pushed past the throng of boys, heading for the entrance to the three-story apartment building.

Fatimah’s running footsteps echoed in the stairway. Omar waited for her at the last step. Taunting boys’ voices came from behind.

‘Saved by big sister!’

‘We’re not going anywhere, Omar!’

‘A real man finishes what he started!’

‘What do you need, Fatimah?’ Omar’s tone showed his impatience.

She shook the front of her dress to keep damp spots from sticking to her legs. ‘I heard what you said. How many times have I told you not to use that kind of language?’

‘I was trying not to use my fists.’

‘You would have, had I not interrupted, right?’

He shifted his weight from side to side. ‘Sorry for cursing.’

‘What were you fighting about?’

He shrugged, failing to look innocent. ‘Nothing.’

Fatimah had her suspicions. Her brother stood out like a sore thumb. Everyone in the neighborhood knew he was not Uncle Mustafa’s blood relative. At least she had the same coloring as his children. Fatimah blended in. But her brother had fair skin, golden red hair and blue eyes. Omar carried himself differently than other boys. He walked with a purposeful stride, furrowing his brows as if concentrating on something in the distance. Rarely smiling, he projected the image of someone in pursuit of a mission.

For reasons unknown to Fatimah, an annoying old woman used to call him ‘the Englishman,’ and the nickname had stuck. Her brother hated it, and she knew it was the reason behind almost every fight he got into. Most likely the cause of this one. She stepped closer to brush dirt from his collar.

‘Look what you’ve done to your school shirt. Go upstairs and take it off so I can wash it and have it ready for tomorrow. How many times have I told you to come straight home and change?’

‘One thousand.’ Omar managed to turn the dutiful answer into an accusation.

Fatimah ignored it. ‘And what happened to your hair?’ She extended her hand to flatten strands shooting up like antennas on top of his head.

He ducked and ran his fingers through his hair. ‘It’s windy today.’

‘Wait a minute.’ She narrowed her eyes. ‘How come you’re out of school?’

‘Don’t you know?’ Omar clasped his hands together. ‘Jamal Abdel Nasser arrived today. Here in Damascus!’ His voice rose with excitement and cracked on the last word. He cleared his throat. ‘Nasser will declare his leadership of the unity with Egypt. Other Arab countries will join the United Arab Republic.’ He inflated his chest and straightened his back, concentrating on a spot behind her left shoulder. ‘We will return to Palestine.’

Omar’s enthusiasm bounced off the walls around Fatimah, his face full of elation, a sparkle dancing in his sky-blue eyes. She tried to maintain a stern expression. ‘So school let out early?’

‘People are gathering in the streets around Al Diafeh Square to see President Nasser. I’m going there.’ He paused, and pointed back with his thumb. ‘Once I’m done with those guys.’

Fatimah wished she could go with him to see the famous leader. Over the past couple of months, Nasser’s presence in Syria was all everyone talked about. Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal two years earlier had brought on the triple aggression by Britain, France and Israel to force his hand. His persistent defiance until foreign troops withdrew from the Suez Canal and Sinai ignited Arab nationalism everywhere, turning him into a great hero. Omar was not alone in his idolization of the daring leader.

Fatimah held Omar’s elbow. ‘Get as close to the president as you can. I want details.’

Omar’s mood shifted. He knotted his brows and drew a long breath. ‘Soon, we will return to our father’s house.’

Something in his tone gave her pause. Something serious, making him seem older than his ten years. What was going on in that boy’s head? He had never mentioned their father’s house before. But again, a fever had gripped the nation, causing people to stay up nights. Was it hope? Had her brother caught it? Glued to the radio almost every evening, he listened to broadcast messages from Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan enquiring about relatives dispersed in other refugee camps. Omar never said a word, but she knew he waited to hear news about surviving members of their family. How could one tell a boy he was the only male survivor? That the continuity of the Bakry name rested on his shoulders, and his alone?

She pushed the idea to the back of her head. ‘Where’s Shareef? Shouldn’t he be out too?’

Omar turned and cast a quick peek outside. He thrust his chin. ‘Shareef’s over there.’

Fatimah stepped around him to see for herself. The neighborhood boys were waiting for Omar; Shareef was standing outside their circle. She raised her index finger in Omar’s face. ‘He had better not get hurt. You know how much it upsets Mama Subhia. You always get him in trouble.’

Omar’s face reddened, as if someone had lit a match under his cheeks. ‘I can’t help it if he follows me around all the time.’

‘Yes, but you’re supposed to watch out for him. Shareef is not as strong as you are.’

‘He’s the older one.’ Omar crossed his arms on his chest. ‘If anything, he should be protecting me.’

‘Really? Three months’ difference?’ Fatimah softened her tone. ‘When did you ever consider him older? You order him around as you please. So next time, send him home before you start a fight, all right?’

Omar raised his brows and opened his mouth to say something.

‘And you shouldn’t fight at all,’ she rushed in. ‘There are other ways to resolve problems.’

A boy’s voice called for ‘the Englishman’ to come out and eat his words.

Omar placed his hands on her shoulders. ‘Don’t worry about Shareef. I won’t let him get hurt.’

He tossed her a rare smile. It went straight to her heart. What would she do with this boy when he turned into a man? Good thing he didn’t smile much. Girls would melt at his feet, and he would be fighting grown men.

‘Don’t ruin your shirt. I expect you inside in exactly five minutes. You need to change before you go to the square.’ She tapped his shoulder. ‘Don’t use your sharp tongue or your fists.’

‘What does that leave me to fight with?’ Omar headed back to the street.

‘Think, Omar,’ she yelled after him. ‘Use your head.’

He did. He walked straight toward the biggest boy in the group and with one head butt knocked him off his feet.

3

Three years later, 1961

When it came to taking care of Mama Subhia’s five children, Fatimah’s maternal nature was second-to-none. The children preferred her loving and quiet disposition to their own stern sister, Huda. Struggling at school, Huda had given up after tenth grade and stayed home. The old midwife took her under her wing, teaching her the ins and outs of her trade, helping her gain a midwife certification when she turned eighteen. Huda became the aging midwife’s right hand and was often called upon in their Palestinian refugee community. Her job made a small dent in the financial burdens of the family.

Fatimah filled the void of the big sister at home and managed to get her high school diploma at the same time. Uncle Mustafa encouraged her to enroll in nursing school, told her he would find a way to pay for it too. But Fatimah knew they couldn’t afford it. With Uncle Mustafa working at the wool factory and Mama Subhia busy having babies, Fatimah had postponed or abandoned some dreams.

‘What do you mean you found a job?’ Mama Subhia asked one evening.

Fatimah walked into the room with a tray of Turkish coffee. She sat on the bed, careful not to disturb baby Salma sleeping by her mother’s side. ‘Um Waleed told me she needed a help

er a couple of hours in the evening.’ Fatimah kept her voice hushed. ‘It’s not far from here.’

‘Um Waleed, the dress maker at the end of the street?’

‘You know her. I’ll be back in time to help you put the children to bed, so it shouldn’t be a problem.’

‘But habibti, you don’t even know how to thread a needle.’ Mama Subhia’s use of the loving word in her motherly tone never failed to make Fatimah feel special.

‘Um Waleed said she will teach me. Besides, she needs me to iron the outfits when they’re done and do simple mending jobs. She’ll pay me for each piece I finish.’ Fatimah leaned forward and stressed her words, ‘Just think about it. I’ll learn a trade and make money at the same time.’

Mama Subhia shook her head. ‘We don’t expect you to make money. If you go to nursing school, you will have a degree and a better paying job.’

Fatimah lowered her eyes to her coffee cup. ‘You know that won’t happen, not any time soon anyway. I’m no better than Huda, and she’s working.’

Baby Salma made a noise in her sleep only her mother could understand.

Mama Subhia placed her hand on her baby’s belly and caressed it. ‘Huda was never interested in school. We had no other options for her. And without Omar, I can’t get Nadia to open a book. The way she depends on him worries me. She’ll turn eleven soon, no longer a little girl.’ Mama Subhia placed her other hand on Fatimah’s cheek. ‘You’re smart, habibti. You can make a future for yourself.’

Fatimah gazed into Mama Subhia’s eyes and felt her warmth spill over. Without an ounce of hesitation, this woman had taken them in after their mother died on the road during their escape and given them a home, treating them like her own children. Sometimes a little better. She owed her a lot, and Omar owed her his life. She could not burden this family with her schooling, and she needed to find a way to cover Omar’s education as well.

‘A few more years and Omar will graduate from high school. I have to think about his future.’ Fatimah drained her coffee cup. ‘If I start working now, I’ll be able to save enough to get him enrolled in the university.’

The baby demanded their attention with a loud cry. Mama Subhia lifted her to her shoulder and patted her back. She kept crying.

Bitter Almonds

Bitter Almonds